Impossible Tasks Outsourced to Perpetuate Imperialism

When creating a product, there’s the planning of the colors and textiles, the concept of the garment itself, the design, and the production. When recreating a product, there is a narrower ideation field. Instead of choosing from the breadth of colors and fabrics, there is meticulous choice between nearly indistinguishable options. For historical costumers, these choices may seem meaningless, but they can have every impact on the finished garment.

Cathy Hay, founder of Foundations Revealed, chose to embark on a journey to recreate a controversial gown, the Worth Peacock Dress. It is an objectively beautiful gown, embroidered with gold thread, which has since deteriorated over time. This deterioration was part of her pitch to recreate it, saying that we have no concept of how beautiful the gown would have been at the time due to paintings fading, the dress itself tarnishing, and photographs not being up to the same standard of quality as they are now.

https://theoldtimey.com/peacock-dress-where-is-it-now/

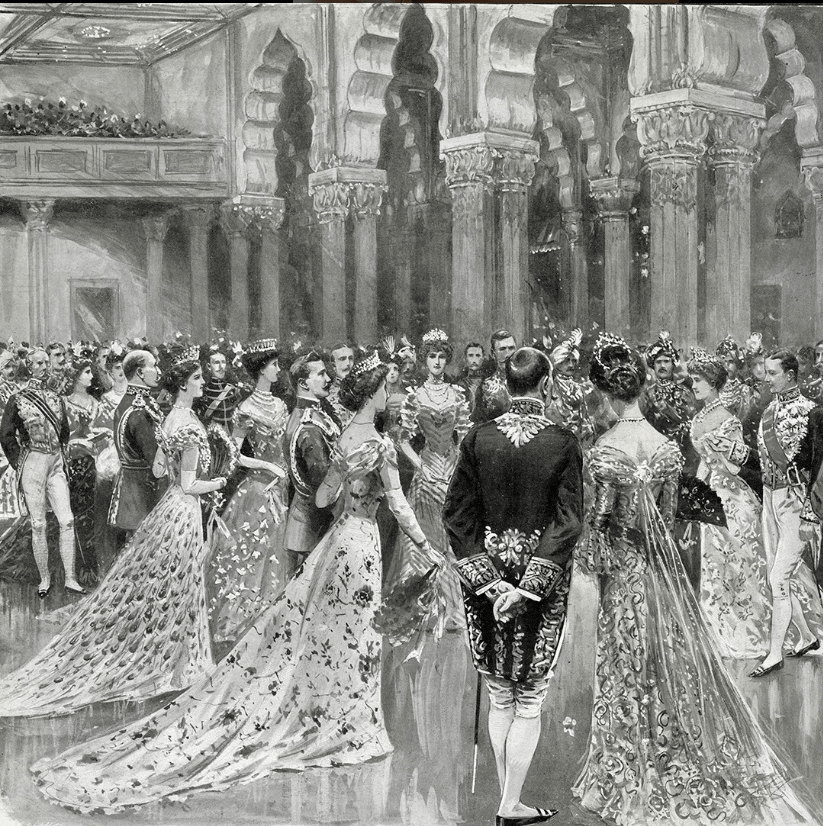

However, This dress was created for the coronation of a British monarch over India in 1903, celebrating their control and subjugation of a place that did not belong to them. It is, essentially, a celebration of colonialism. As beautiful as the gown is and could be, this history is impossible to divorce from the garment. Mary Curzon herself was a striking six feet tall, and her choice to commission this gown was deliberate. She wanted to display Indian embroidery, and was instrumental in the integration of it into Western fashions of the time. The embroidery that covers the entire gown was created by specialists in a specific style called zardozi, forcing them to display their talents in service of a regime they did not want to live under. Colonialism in that form may have ended in 1947 (76 years ago), but the aftereffects of imperialism are still felt today.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CUDPWM9rEp9/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

When Hay began the project, she had called it an “Impossible Task”. And perhaps, had she done it herself, it would have been. A singular person recreating the backbreaking work of what was likely an entire group of people would have been a herculean effort. But after attempting a portion of the embroidery on her own, she nearly gave up on the project.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B1ZZoXPgGEI/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

Here is where anyone who is involved in the larger production industry would say to outsource the production.

And in fact, Bernadette Banner, a fellow “costuber”, made that very same suggestion. Banner has been involved in creating garments for Broadway productions, and received a degree from the Design and Production Studio at Tisch School of the Arts, followed by her internship for Jenny Tiramani at the School of Historical Dress in London. All this to say, Banner has been formally educated on the creation of garments, and was likely taught about outsourcing production, as any fashion student is. She was the one to connect Hay to an Indian embroidery artist, and promoted the project on her own channel in a now-deleted video. The decision to outsource the labor was, effectively, a prescription to mend the problem that was the creation of the most difficult aspect of the gown.

As a Worth gown, it was sewn by the son of Worth himself, but all of the fabric (chiffon!) was embroidered in India, shipped to Paris for Worth’s son to sew, and then shipped as a finished product back to India to be worn. Hay’s new decision to replicate this process was what drew her under fire.

The community of CosTube (an abbreviated form of Costume Youtube) does have a largely white population. But several members of color had made it known that they did not approve of this project from the beginning. The tipping point, however, was the outsourcing. It becomes no longer an “impossible task” of labor and time but rather simply an expensive task- which required fundraising, and people contributed thousands of dollars to see this dress be recreated.

Evidently Hay got a sample from Mayankraj Singh from Atelier Shiaarbagh, where they have been doing zardozi for seven generations. With the gown being made in 1903, that is a total of 120 years ago. Dividing that number by 7 gives about 17 years, so even if they were rather short generations, there is a high likelihood that this very same shop was doing this very same embroidery at the time that the gown was made. However, Singh’s head embroiderer burned the sample and said they would not make it. Hay’s response was to abandon the project entirely.

The backlash from other (primarily white) creators was that calling out this project meant the end of historical recreation as a whole, and that cancel culture was going to ruin the community. But this project in particular was of a piece that was created to showcase the skill of workers who had no say in their ruler. Recreating this piece using those same workers, as a person who is a member of the oppressing country, is clearly a poor choice, even if this piece was created solely to display (it was not, she intended to wear it). There were many other avenues to embark down- continue making the embroidery herself, choosing another gown to create, or even creating a gown using the same techniques and practices that was not an exact recreation of one so widely known as a symbol of hatred.

Just as this project’s cancellation is not the cancellation of every historical sewing endeavor, this outsourcing being the morally wrong decision is not to say that every outsourcing project is inherently wrong. There are skilled artisans in every part of the world, and as long as they are paid fairly for their skill as well as their time, and credited in the finished piece, there is no reason to avoid calling upon their services if they are willing to provide them. Outsourcing is a vital part of most fashion production, as the vast majority of designers don’t have their own manufacturing facilities. But its vitality should not place it in a realm above scrutiny.

Outsourcing production is neither inherently good or bad, and its commonplace nature can allow it to become a “necessarily evil” rather than a well thought out and fairly negotiated business practice.

Hay’s unscrupulous writing and fundraising practices are detailed by Beth Winegarner and azteclady so I will not repeat them, as they covered them more thoroughly and with more nuance than I would have, and are not relevant for my focus on production. Likewise, Bernadette’s level of involvement was not relevant to me beyond the initial push to outsource, though I do appreciate that she apologized and was transparent about where the fundraising money ended up.

Leave a comment